Trichomes, those little tiny crystal-like hairs that cover the buds, hold all the good stuff. The different methods of hashmaking focus on isolating these sticky little parts of the cannabis plant because they house the majority of its resin.

Every part of the cannabis plant has at least a little THC in it. Leaves have around 4%, while buds have up to 25% or 30% of dry weight. The trichomes cover all parts of the buds, from the interior stems to the surrounding leaves.

Scientists used to think that THC and other cannabinoids were made in the green plant tissue and transported out to the trichomes during flowering, but after intensive research, they realized that the trichomes themselves make the cannabinoids and terpenes.

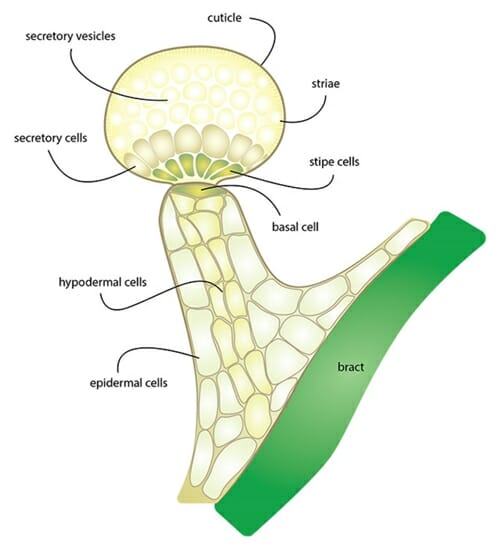

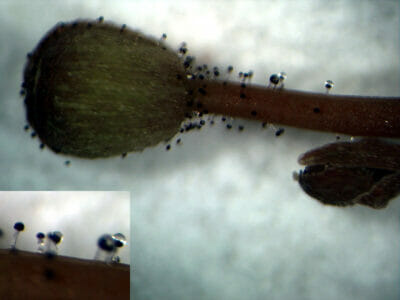

Trichomes might grow off a leaf around the flower of a female plant, or a bract (pictured above). A bract houses the seeds in a fertilized plant, and has a high density of trichomes. Looking closely, you’ll see six different types of these glands are all oozing resin during flowering, but the biggest ones with the most juice are the capitate stalked trichomes.

At about 50 to 100 micrometers wide, trichomes are very small. Zoom in close enough and you can see the individual cells that make up the structure.

Capitate stalked trichomes have two main parts: the stalk and the gland head.

The epidermal cells hold up the mature trichome forming the outside of the stalk, and a continuous layer extends over the entire bract surface. The hypodermal cells on the inside of the stalk constantly transport nutrients (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phloem) to the gland head. The basal cell at the top of the stalk holds on to the gland head. As the flower matures, and as mature flowers dry, this connection weakens and gland heads tend to fall off.

At the base of the gland head are stipe cells, which hold up the secretory cells. Secretory cells take the nutrients from the phloem and turn them into precursors for cannabinoid and terpenoid metabolism. The theory is that these precursors get transported to the secretory vesicles above, and are converted into cannabinoids and terpenoids once they’re there.

As the gland head churns out its product, the resin gets deposited, and up close to the cuticle, the outer layers of trichome surface. The cuticle, thickens getting richer and richer in oil as flowering progresses.

The essential oils, including THC, mostly accumulate on the outer layer of the gland head, but also on the outer layer of the epidermal cells that cover the entire bract, or any trichome-dense area. Resinous THC also accumulates in the fibrillar matrices (pardon the jargon) of the secretory vesicles. Inside these vesicles there is some THC, but also high amounts of terpenoids, which are less viscous.

The presence of THC mostly on the outside of the plant is great news, but no surprise; extractions on unadulterated bud work spectacularly well because of this fact. While grinding up flowers makes them easier to work with for cooking or small-scale extractions, it’s not necessary for getting a high yield.

*This article has been modified from it’s original source.(Originally printed in High Times Magazine) By Sirius J March 27, 2015 http://hightimes.com/grow/the-anatomy-of-a-trichom..

Trichomes (/ˈtraɪkoʊmz/ or /ˈtrɪkoʊmz/), from the Greek τρίχωμα (trikhōma) meaning “hair“, are fine outgrowths or appendages on plants, algae, lichens, and certain protists. They are of diverse structure and function. Examples are hairs, glandular hairs, scales, and papillae. A covering of any kind of hair on a plant is an indumentum, and the surface bearing them is said to be pubescent.

Algal trichomes

Certain, usually filamentous, algae have the terminal cell produced into an elongate hair-like structure called a trichome. The same term is applied to such structures in some cyanobacteria, such as Spirulina and Oscillatoria. Cyanobacteria trichomes may be unsheathed, as in Oscillatoria, or sheathed, as in Calothrix.[1] These structures play an important role in preventing soil erosion, particularly in cold desert climates.[citation needed] The filamentous sheaths form a persistent sticky network that helps maintain soil structure.

Plant Trichomes

Aerial surface hairs

Trichomes on plants are epidermal outgrowths of various kinds. The terms emergences or prickles refer to outgrowths that involve more than the epidermis. This distinction is not always easily applied (see Wait-a-minute tree). Also, there are nontrichomatous epidermal cells that protrude from the surface.

A common type of trichome is a hair. Plant hairs may be unicellular or multicellular, branched or unbranched. Multicellular hairs may have one or several layers of cells. Branched hairs can be dendritic (tree-like) as in kangaroo paw (Anigozanthos), tufted, or stellate (star-shaped), as in Arabidopsis thaliana.

Another common type of trichome is the scale or peltate hair, that has a plate or shield-shaped cluster of cells attached directly to the surface or borne on a stalk of some kind. Common examples are the leaf scales of bromeliads such as the pineapple, Rhododendron and sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides).

Any of the various types of hairs may be glandular, producing some kind of secretion, such as the essential oils produced by mints and many other members of the family Lamiaceae.

In describing the surface appearance of plant organs, such as stems and leaves, many terms are used in reference to the presence, form, and appearance of trichomes. The most basic terms used are glabrous—lacking hairs— and pubescent—having hairs. Details are provided by:

- glabrous, glabrate – lacking hairs or trichomes; surface smooth

- hirsute – coarsely hairy

- hispid – having bristly hairs

- articulate – simple pluricellular-uniseriate hairs

- downy – having an almost wool-like covering of long hairs

- pilose – pubescent with long, straight, soft, spreading or erect hairs

- puberulent – minutely pubescent; having fine, short, usually curly, hairs

- pubescent – bearing hairs or trichomes of any type

- strigillose – minutely strigose

- strigose – having straight hairs all pointing in more or less the same direction as along a margin or midrib

- tomentellous – minutely tomentose

- tomentose – covered with dense, matted, woolly hairs

- villosulous – minutely villous

- villous – having long, soft hairs, often curved, but not matted

Hairs on plants are extremely variable in their presence across species and even within a species, such as their location on plant organs, size, density, and therefore functionality. However, several basic functions or advantages of having surface hairs can be listed. It is likely that in many cases, hairs interfere with the feeding of at least some small herbivores, and, depending upon stiffness and irritability to the palate, large herbivores as well. Hairs on plants growing in areas subject to frost keep the frost away from the living surface cells. In windy locations, hairs break up the flow of air across the plant surface, reducing transpiration. Dense coatings of hairs reflect sunlight, protecting the more delicate tissues underneath in hot, dry, open habitats. In addition, in locations where much of the available moisture comes from fog drip, hairs appear to enhance this process.

Root hairs

Root hairs, the rhizoids of many vascular plants, are tubular outgrowths of trichoblasts, the hair-forming cells on the epidermis of a plant root. That is, root hairs are lateral extensions of a single cell and only rarely branched. Just prior to the root hair development, there is a point of elevated phosphorylase activity.[clarification needed] Root hairs vary between 5 and 17 micrometres in diameter, and 80 to 1,500 micrometres in length (Dittmar, cited in Esau, 1965). Root hairs can survive for two to three weeks and then die off. At the same time new root hairs are continually being formed at the top of the root. This way, the root hair coverage stays the same. It is therefore understandable that repotting must be done with care, because the root hairs are being pulled off for the most part. This is why planting out may cause plants to wilt.

Significance for taxonomy

The type, presence and absence and location of trichomes are important diagnostic characters in plant identification and plant taxonomy.[2] In forensic examination, plants such as Cannabis sativa can be identified by microscopic examination of the trichomes.[3][4] Although trichomes are rarely found preserved in fossils, trichome bases are regularly found and, in some cases, their cellular structure is important for identification.

Uses

Bean leaves have been used historically to trap bedbugs in houses in Eastern Europe. The trichomes on the bean leaves capture the insects by impaling their feet (tarsi). The leaves would then be destroyed.[5]

Trichomes are an essential part of nest building for the European wool carder bee (Anthidium manicatum). This bee species incorporates trichomes into their nests by scraping them off of plants and using them as a lining for their nest cavities.[6]

Defense

Plants may use trichomes in order to deter herbivore attack via physical and/or chemical means, e.g. in specialized, stinging hairs of Urtica (Nettle) species that deliver inflammatory chemicals such as histamine. However, some organisms have developed mechanisms to resist the effects of trichomes. The larvae of Heliconius charithonia, for example, are able to physically free themselves from trichomes, are able to bite off trichomes, and are able to form silk blankets in order to navigate the leaves better.[7]

See also

References

- Jump up

^ “Identify That Alga”. Retrieved September 20, 2013. - Jump up

^ Davis, P.H.; Heywood, V.H. (1963). Principles of angiosperm taxonomy. Princeton, New Jersey: Van Nostrandpage. p. 154. - Jump up

^ Bhatia, R.Y.P.; Raghavan, S.; Rao, K.V.S.; Prasad, V.N. (1973). “Forensic examination of leaf and leaf fragments in fresh and dried conditions.”. Journal of the Forensic Science Society. 13 (3): 183–190. doi:10.1016/S0015-7368(73)70794-5. - Jump up

^ United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2009). Recommended Methods for the Identification and Analysis of Cannabis and Cannabis Products (Revised and updated). New York: United Nations. pp. 30–32. ISBN 9789211482423. - Jump up

^ Szyndler, M.W.; Haynes, K.F.; Potter, M.F.; Corn, R.M.; Loudon, C. (2013). “Entrapment of bed bugs by leaf trichomes inspires microfabrication of biomimetic surfaces” (PDF). Journal of The Royal Society Interface. 10 (83). doi:10.1098/rsif.2013.0174. ISSN 1742-5662. - Jump up

^ Eltz, Thomas; Küttner, Jennifer; Lunau, Klaus; Tollrian, Ralph (6 January 2015). “Plant secretions prevent wasp parasitism in nests of wool-carder bees, with implications for the diversification of nesting materials in Megachilidae”. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 2. doi:10.3389/fevo.2014.00086. - Jump up

^ Cardoso, Márcio Z. “Ecology, Behavior and Binomics: Herbivore Handling of a Plant’s Trichome: The Case of Heliconius Charithonia (L.) (Lepidoptera:Nymphalidae) and Passiflora Lobata (Kilip) Hutch. (Passifloraceae).” Neotropical Entomology 37.3 (2008): 247-52. Web.

- Esau, K. 1965. Plant Anatomy, 2nd Edition. John Wiley & Sons. 767 pp.